The above photograph shows CNR 6218, a Confederation class U-2-g Northern built by Montreal Locomotive Works in 1942 (if you do not see a steam locomotive working hard upgrade then click on the post title ).

The image cannot be reliably dated but I believe it was taken on Canada Day in the summer of 1968. During the late 1960’s the Upper Canada Railway Society hosted annual “Railway Days” steam excursions out of Belleville, Ontario, running the train north along an old Grand Trunk Railway spur that ran up through Madoc and Stirling. The train turned on the wye at Hastings before heading back to Belleville to start another round trip.

I travelled to Belleville with my Dad who was a big fan of steam and all things mechanical. Since he was a Professional Engineer he was able to explain the operation of almost any mechanical device to me. I learned the difference between Walschaerts and Stephenson valve gears at an early age (who today knows the application of a Fly-Crank Rod or a Radius Bar?), understood the design of triple expansion steam engines, could describe the operation of a Scherzer rolling lift Bascule bridge, and a thousand other forms of arcane mechanical ephemera.

The photograph was taken at a location off Moira Road near Huntington Station. The station, if there ever was one, was long gone, but the location made for a great image as 6218 stomped up the hill to Hastings. Thinking back, I feel sorry for my Dad who spent long hours driving the backwoods to reach photo locations and was then abandoned in the car as I hiked overland through the fields in order to get closer to the tracks.

My first photographs were of steam engines. I had found an old Zeiss Ikon folding camera in a household closet and had brought it with me on a family vacation that took us to Mount Washington, New Hampshire. We visited the cog railway base station and I had my parents purchase my first roll of film, a roll of Kodak 620. The emulsion was panchromatic but the camera was likely a pre-war design. It had a small rubylith window on the back so that you could read off the frame numbers when using the manual film advance knob. But almost all post-war consumer emulsions were panchromatic. This meant all of my images fogged in camera and delivered an ethereal effect that is now only obtainable via a software tool that costs hundreds of dollars. What was once a free, and unwanted, image defect is now an expensive desired image attribute. That is progress.

In 1965 my Christmas present was a Yashica SLR with a 42mm screw mount Yashinon 50mm lens. This camera also incorporated a CdS cell just below the top deck under the film advance lever. This was not coupled in any way and you needed to actuate the meter and then set an appropriate f stop and shutter speed. The old Zeiss Ikon had required the use of a separate light meter, an item I had also found buried in the closet – a small selenium cell meter which I used in preference to the built in CdS cell on the Yashica. CdS was known to be subject to “blinding.” Selenium meters did not have this problem.

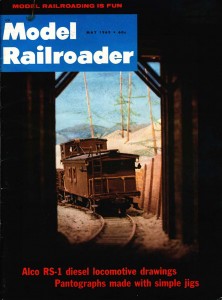

Model Railroader cover photograph

In 1967 I earned $50 by selling a cover image to the magazine Model Railroader. The cover image is shown above. This scene was photographed on a table top diorama that I built in a corner of my bedroom. You cannot tell from the image but I borrowed from the ancient Greeks; the tunnel portal was not built to scale but was carefully crafted to help deliver the desired perspective. The terrain in the background is composed of plaster and sawdust, the trees were constructed of asparagus fern fronds preserved in a glycerine solution and then glued into holes drilled in the sides of tapered and stained basswood dowels. The distant mountain range and sky were painted on a curved backdrop. The rail is hand spiked code 70 stained nickel silver on a roadbed of individual ties ballasted with simulated gravel.

The hardest work was building the caboose and the gondola car. There was a great deal of detail work (you may not be able to see it but a scale human figure is seated in the caboose cupola with his arm resting on the open window sill) and this took an incredible amount of time to complete.

I was quite excited to be earning money with the camera and I made a number of submissions to the Montreal Star which ran a full page reader provided image in the weekend colour insert. I received a very nice rejection letter for my efforts; I suspect the editor recognized that I was an ambitious youngster.

By 1969 I had dismantled the diorama and built a full darkroom in its place. I then began to teach myself black and white photography. I mixed all my own chemicals, developed my own film, and made prints of the best negatives. There was great magic in watching the image come up in the developer bath. Print washing was a tedious task as it had to be done manually (but I did it well as, after 45 odd years, none of the prints show any sign of yellowing due to residual silver nitrate). The part I really disliked were the hours spent in the dark breathing chemical fumes. There was no domestic air conditioning in those days and you cannot easily open a window in a darkroom, so the work was also uncomfortably hot in summer.

I attended local gymkhana’s and other sports events and sold prints to the participants. I doubt I made much money doing this. In fact I question if I fully covered my cost of materials. I also shot a lot of images for the Hudson High School class yearbook and submitted another set of images to the Montreal Star. These pictured a group of fellow students assisting a recent motor vehicle accident victim in cleaning house. I was very proud of these prints. The interior shots avoided the use of fill flash and relied on my budding skills as a printer to hold the back the daylight at the windows and still present full shadow detail in the interior. I took my cue from some of Eugene Smith’s work and felt the images worked well to convey the sombre mood of the day.

When I moved out to Vancouver in the early 1970’s, my camera, an early model Nikon F, was stolen through an open window. I was living with a woman at the time and we were thinking of marriage but she was uncomfortable with my work routine which involved two week tours on Search and Rescue cutters. Plus an incident occurred which made her uncomfortable about my line of work.

We had a small top level apartment on Cornwall Street. It’s best feature was an octagonal turret which looked out over English Bay. This became our bedroom after I converted the actual bedroom into another darkroom. I spent a lot of time teaching myself colour film development and printing. We had friends in the Kootenay’s and we were thinking of relocating there and I was contemplating opening a commercial photography business.

I was doing a lot of work with both medium format and a 4″x5″ view camera. I also attempted to perfect my skills in dye transfer printing. The dye transfer process utilized a set of matrices which were contact “printed” to a receptor sheet. The process offered a unique degree of control over colour values in the final image. The problem was that this degree of control mandated extremely close process tolerances. Any variation in either PH or temperature would impact the image.

My difficulty arose from my home built darkroom. It had no running water. This was acceptable for black and white work but not for dye transfer which required a fixed temperature water bath to maintain solution temperatures. It became impossible to continue as I realized I needed a water chiller to bring temperatures down.

The aspiration to open a commercial photography studio died when the relationship broke up. I sold all of my camera gear to finance another venture (thanks to the sudden appreciation of the Japanese yen around this time I was able to sell my gear in used condition for more than I had paid for it). This was the end of my photographic adventures until the time Colin was born.

While I have a considerable background in photography, I am not sure what occupational opportunity currently exists. The fact that every cell phone is also a camera has made everyone a photographer. Analog imaging has been almost completely displaced by digital. The range of photographic papers and film emulsions has contracted considerably. Dye transfer materials are no longer available. Digital has resulted in an entirely new aesthetic. What was once a highly skilled technical craft has now been democratized and facilitated by improved technology, and an entirely new set of image defects are now accepted and prized.

From what I am able to learn of the current status of commercial photography it is a contracting market. A great many images are available via stock agencies, there are a large number of amateur photographers with the skill and equipment to underbid a professional, a greater proportion of commercial images are taken by other than professional photographers, and press photographers are being laid off.

I am able to do digital image processing but I am unsure of the demand for this skill. There is a very big difference between operating in a time constrained commercial environment and my current situation in which I must devote an extreme number of hours to crafting these blog posts and the accompanying images.

I have the hope that constant repetition will make me faster but this does not appear to be happening.

Update 03/06/14

A photographer must travel to the location of the photo shoot. To undertake this job requires both a car and the competence to travel widely within the city. A photographer will also need to be extremely good at scheduling, and juggling multiple daily appointments in order to maximise revenue.

Due to the injury I seek to reduce my automobile travel to the minimum, feel uncomfortable traveling beyond my known routes, and arrive an hour early for every appointment so as to avoid time pressures which tend to provoke errors.